Until 2010, the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive (IPPC) IPPC-D 96/61/EC of 24 September 1996, amended in 2001 (consolidated IPPC-Directive 2008/1/EC of 1 January 2008) was the EU’s main regulatory instrument to tackle harmful emissions into the environment.

The IPPC framework was replaced by the Industrial Emission Directive (IED) 2010/75/EU on 24 November 2010, strengthening the legislation that implements IPPC and six other directives on industrial emissions. The main changes brought by the IED 1.0 to the consolidated 2001 IPPC Directive are summed up in the EEB briefing of 2011.

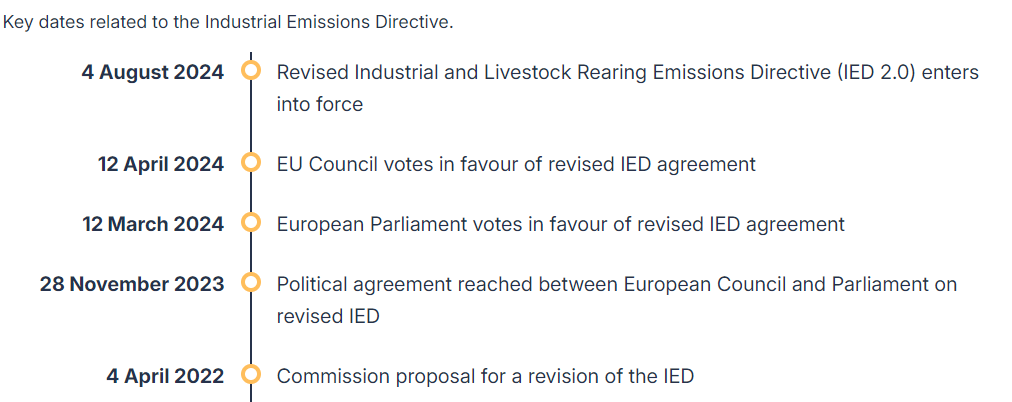

A review of the IED 1.0 took place between April 2022 and April 2024.

(source European Commission)

The Industrial Emissions Directive or IED (2.0) is the main EU instrument setting environmental standards for large scale industrial activities. The IED aims to achieve a high level of protection of human health and the environment taken as a whole, including climate protection, by preventing pollution at source from industrial activities across the EU, in particular through stricter and better application of Best Available Techniques (BAT).

The IED covers the activities of about 37,000 industrial installations and about 28,500 large scale pig and poultry rearing “farms” (see Annex I for the scope covered).

The key provisions, stemming from the IPPC-Directive, relate to the BAT concept for permit conditions, inspection and monitoring requirements as well as public participation in decision making, access to information and justice and are in its Chapter II. Alongside those common requirements, the IED sets minimum binding limits for a set of large-scale industrial activities. Those minimal requirements stem from the 6 sectoral directives on industrial activities and are commonly known as the “EU Safety net”. Those minimal provisions are set in its Chapters and Annexes: Ch3 / Annex V relates to Large Combustion Plants, ChIV / Annex VI relates to Waste (co)incineration, Ch5 / Annex VII relates to activities using organic solvents, Ch6 / Annex VIII relates to titanium dioxide production. Those EU safety net provisions set minimal requirements relating to monitoring, emission limit values etc that should not be exceeded but are not based on Best Available Techniques. Considerable weakening of provisions have been provided for industrial scale livestock rearing activities (see new Chapter Via)

All installations covered by the IED are required to hold a permit issued by national or local responsible authorities. The key principle is set in Article 1, which is to lay down rules on integrated prevention and control of pollution arising from industrial activities.

The rules are designed to prevent or, where that is not practicable, to continuously reduce emissions into the air, water and land and to prevent the generation of waste, improve resource efficiency, and to promote the circular economy and decarbonisation. The ambition is to deliver a high level of protection of human health and the environment taken as a whole – the so called “integrated approach” to prevent pollution in a coherent manner and not to shift impacts from one media to the other. Permit conditions are to be based on the performance levels achieved with Best Available Techniques (BAT) and contained in a reference document called a ‘BREF’, which shall be the basis for permitting.

The IED 2.0 also provides requirements linked to:

- Inspections, non-compliance and penalties (inspection related aspects are largely unchanged but issues linked to non-compliance tightened, such as minimal penalties);

- Access to information and environmental reporting (see section on ‘Improved reporting on industrial activities);

- Public participation in decision making and access to justice;

- Compensation right(s) in case of illegal pollution (see dedicated briefing of ClientEarth)

- Water protection rules, tightened mainly for indirect discharges.

The main changes, be they positive or negative and opportunities ahead are summed up in the policy briefing of the EEB of April 2024.

The following main ‘crosscutting’ aspects are highlighted here:

- Permit writers and Member must ensure that strictest achievable emission limit values are set based on best overall performance the installation can achieve

Under IED 1.0 the default approach of permit writers was to aligning emission limits values (ELVs) to the lax (upper range) BAT levels in the implementation phase. In the future, the competent authority shall set the ‘strictest achievable ELVs, and this shall relate to the analysis of the feasibility of meeting the ‘strictest end of the BAT-AEL range and demonstrating the best overall performance that the installation can achieve’. A further added value is also expected for the countries setting BAT standards through national-level rules, so-called general binding rules (GBR). Therefore, and by analogy, the ministries in charge must consider the strictest achievable emission limit values and demonstrate best performance for categories of installations having similar characteristics (typically sectoral legislation). This is an important change to drive standards and national rules towards more ambition. Many countries such as Austria, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden, make use of those GBR.

On the downside however, the ‘technical feasibility assessment’ will depend on case-by-case permit reviews that will have to be performed by the operator, which can easily argue that it is not ‘feasible’ (from a profit margin maximisation perspective) to apply stricter emissions levels, despite those being judged as economically viable conditions based on outdated information pre-dating a decade prior to effective application of those standards. There are no rules for the timing of providing such non-feasibility assessments and how to make those transparently available and subject to public scrutiny.

- Installation-level ‘Transformation Plans’ towards a clean, circular and climate neutral production (by latest 2050)

One of the most forward-looking provisions is for the operator to set out a’ transformation plan’ (TP) on how the installation will transform itself during the 2030-2050 period to contribute to the emergence of a sustainable, clean, circular, resource efficient and climate-neutral economy by 2050, including deep industrial transformation. The TP must be provided by latest 30 June 2030, and it shall be integral part of the Environmental Management System. However, it is for environmental verifiers (auditors) to assess the conformity of the plans with the requirements and minimal content by 30 June 2031 only, as set within a Commission delegated act to be provided prior to 30 June 2026.

The key shortcoming of this provision is the absence of clear and measurable key performance indicators as to what the meaning of ‘clean’/‘circular’ actually is for the sector concerned. There is a risk that this becomes a tick-box exercise without any screening as to the ambition and seriousness of the ‘plans of good intentions’ set out by the operators. See specific EEB input made on the usefulness of the transformation plans here (March 2025).

- Trading off people’s health and empty shell compensation rights but minimal sanctions to fight for at national level

While the initial proposal aimed at strengthening the right to compensation for victims of illegal pollution and sanctions have been weakened substantially, some overall improvements in this area have been made. NGOs had demanded a strengthening of the existing penalties provision by setting turnover-linked minimum levels for financial penalties. The final deal is set to at least 3% of the annual Union-wide turnover of the operator in the financial year preceding the infringement year but only for “most serious infringements” (Art 79). This is the first time in environmental law that the EU did agree on a new compensation right for citizens affected by illegal pollution (Art 79a).

All now depends on transposition: Member States will have to ensure the principle of effectiveness – it must therefore truly be possible in practice to obtain compensation before courts in appropriate cases.

For readability reason, we decided to present the challenges and opportunities ahead for the respective thematic areas in the respective ‘Environmental issues’ section.

The EEB, together with its members and partners has been actively involved in all critical steps of the processes so far which led to the IED 2.0.

The main inputs made during co-decision were as follows:

- Input to the first impact assessment (2019)

- Input to (second) technical input to the Targeted Stakeholder Surveys (2021).

- Joint position on IED and IEP-R (pre-proposal stage 2022)

- Intensive livestock Briefing (2022)

- Circular Economy Position Paper (2022) Circular Economy Briefing (2022)

- Innovation Briefing (2022)

- Climate Protection Briefing (2022)

- Enforcement Briefing (2022)